There’s finally an answer.

Morning sickness, a well-known pregnancy side effect characterized by nausea and vomiting in the initial trimester, appears to be closely linked to a singular hormone, according to recent research conducted by the University of Cambridge and published in the journal Nature.

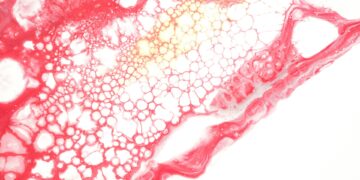

This groundbreaking discovery, centered around a protein named GDF15 produced by the fetus, sheds light on potential avenues for more effective morning sickness treatment, especially in severe cases. While the findings don’t present an immediate path for pharmaceutical applications, they offer a promising direction for future research and development.

The study indicates that GDF15 is responsible for inducing nausea and vomiting in approximately seven out of ten pregnancies. The severity of these symptoms is directly correlated with a woman’s exposure to the hormone before pregnancy and the amount produced by the fetus. Notably, limited exposure before pregnancy can lead to hyperemesis gravidarum, a severe form of first-trimester sickness that can result in hospitalization due to dehydration and, in extreme cases, even death.

The research suggests that enhancing a woman’s exposure to GDF15 before pregnancy could increase her resilience to the hormone, potentially reducing the severity of morning sickness. GDF15 is produced at low levels in non-pregnant tissues, but a higher concentration in the placenta seems to be an evolutionary feature in certain species, signaling to the mother’s brain about the potential infectious risks in specific foods during early pregnancy.

While the study proposes a direct link between GDF15 and morning sickness, caution is warranted, as there is considerable overlap between symptomatic and asymptomatic women. GDF15 levels alone may not be the sole determinant of susceptibility. Experts, including Dr. Kecia Gaither, emphasize the need for further research to delve into manufacturing considerations, dosage, preparation, and pharmacokinetics of this hormone before implementing it as a treatment.

Dr. Gaither points out that translating these findings into a viable treatment will require time and additional research. The study’s suggestion that exposing women to the hormone in a non-pregnant state could prevent hyperemesis gravidarum needs further validation. In essence, the study raises intriguing possibilities for understanding and managing morning sickness, but definitive treatments may still be years away from realization.

Discussion about this post