The Missing Vitamin That Could Protect Against Stroke

If you’ve ever reviewed a food’s nutritional label or checked a supplement bottle, you’ve probably noticed a recommended daily amount for each vitamin and mineral. In the U.S., the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine establishes these Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs), which are designed to meet the needs of almost all healthy individuals. However, recent research suggests that the RDA for vitamin B12 might be too low, potentially leaving individuals at risk for cognitive decline, dementia, and stroke.

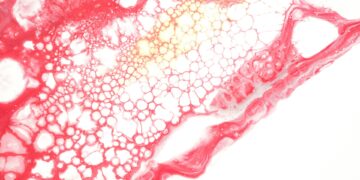

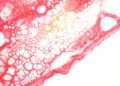

Vitamin B12 plays a vital role in red blood cell production, nerve function, and DNA synthesis, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Foods rich in vitamin B12 include beef liver, clams, oysters, salmon, tuna, ground beef, milk, and yogurt. Many people also take B12 supplements to meet their daily intake.

Inadequate B12 intake can result in symptoms like fatigue, numbness, tingling, anemia, infertility, glossitis (painful mouth or tongue sores), and pale or yellowish skin. Research has long linked low levels of B12 to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Elevated homocysteine levels, a byproduct of protein creation in the blood, are often associated with B12 deficiency. Homocysteine, along with vitamins B6 and folate, is typically broken down by B12, and a deficiency can lead to elevated homocysteine levels that may harm arteries, increasing the risk of blood clots, heart attack, or stroke.

A new study published in Annals of Neurology suggests that the current RDA for B12 might not be sufficient to prevent cognitive decline. The study involved 231 healthy elderly individuals with an average age of 71.2 years, whose vitamin B12 levels were well above the RDA of 148 pmol/L. Despite having an average of 414.8 pmol/L, which is considered “normal,” researchers found several concerning outcomes. Participants with lower B12 levels exhibited slower processing speeds and reaction times in cognitive tests. Additionally, MRI scans revealed increased white matter in the brain, which could impair memory, balance, and mobility, and increase the risk of stroke and dementia.

The study’s authors, including Dr. Ari J. Green, emphasized that current B12 guidelines may overlook subtle neurological changes in individuals with levels considered normal. They suggest that clinicians should consider B12 supplementation for older adults with neurological symptoms, even if their levels fall within the normal range. They also call for more research into the biological effects of B12 insufficiency, which may be a preventable factor in cognitive decline.

Discussion about this post