A miracle shot exists now.

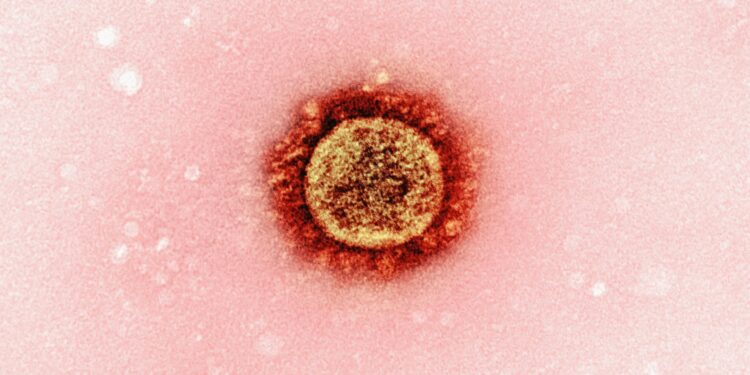

The United States has approved the world’s first twice-a-year injectable medication for HIV prevention, offering a potentially game-changing option in the fight against the virus. The new drug, called lenacapavir and marketed for prevention as Yeztugo, is designed to provide long-lasting protection from HIV with just two doses annually. Clinical trials have shown it to be highly effective, outperforming daily oral PrEP options, especially among high-risk groups. This development could expand access to HIV prevention for people who struggle with daily adherence or face stigma related to taking pills.

Despite its promise, the rollout of Yeztugo faces significant challenges both in the U.S. and globally. Funding cuts to public health programs and the dismantling of HIV outreach infrastructure in recent years have raised concerns about the drug’s accessibility. Experts warn that even with such a powerful tool, real progress depends on whether healthcare systems can reach vulnerable populations consistently. Insurance coverage is expected to help, though legal and political uncertainties, such as a pending Supreme Court case, could limit access for many Americans.

Clinical trials in Africa, the U.S., and other high-prevalence regions demonstrated exceptional effectiveness. Among young women in South Africa and Uganda, none of the participants receiving lenacapavir contracted HIV, compared to infections among those on daily PrEP pills. A separate study showed similarly strong results among gay men and gender-diverse individuals. For many, the convenience of only needing protection twice a year may be key to maintaining prevention over time.

Globally, Gilead Sciences—the manufacturer—has partnered with generic producers to provide low-cost versions of the drug to 120 low-income countries. The company pledged to offer the medication at no profit until generics are available. However, concerns remain that middle-income countries may be excluded from these affordability plans. Health advocates argue that universal access is essential if the drug is to have a meaningful impact on the HIV epidemic.

While lenacapavir represents a major advancement in HIV prevention, experts emphasize that medicine alone is not enough. Ensuring widespread, equitable access will require renewed investment in healthcare infrastructure, public education, and political will. Without addressing these systemic gaps, the potential of this new tool could remain largely untapped.

Discussion about this post