A link has been found.

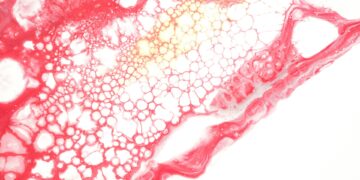

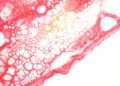

A recent study has revealed that exposure to ozone pollution in early childhood significantly raises the risk of developing asthma and experiencing wheezing by the time children reach ages 4 to 6. The research, published on April 2 in JAMA Network Open, indicates that even modest increases in ozone levels during a child’s first two years can have a measurable impact on respiratory health later in early childhood.

The findings are based on data from over 1,100 children across six U.S. cities: Minneapolis, San Francisco, Seattle, Memphis, Rochester, and Yakima. Researchers compared local ozone levels, drawn from federal environmental data, with health reports provided by the children’s mothers. They discovered that a 2 parts per billion increase in ozone exposure was linked to a 31% rise in asthma risk and a 30% rise in wheezing between ages 4 and 6. Interestingly, the study did not find a similar correlation for children aged 8 or 9, a result the researchers found difficult to explain.

Lead author Logan Dearborn, a doctoral candidate at the University of Washington, noted that the relationship between ozone and asthma was especially evident when other pollutants, like fine particulate matter, were also present at higher levels. The study found that ozone had a stronger influence on asthma risk when levels of fine particulate matter were above the median, suggesting that the interaction between different pollutants might amplify health risks.

Ozone is a common pollutant formed when sunlight interacts with emissions from vehicles, power plants, and industrial sources. It is one of the most frequently exceeded air quality standards in the United States. While past studies have linked childhood asthma to other air pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide and particulates, this study provides new insights into how ozone may independently contribute to asthma development.

The researchers called for greater attention to long-term ozone exposure in public health policy. Currently, U.S. regulations focus mainly on short-term ozone levels. Dearborn suggested that revisiting and potentially expanding these regulations could help better protect children from long-term health impacts.

Discussion about this post