This is an amazing breakthrough.

Scientists have identified a naturally occurring protein that may reverse cataracts, based on studies conducted in rats and hibernating squirrels. Though animal research doesn’t always directly translate to humans, the discovery of the RNF114 protein offers hope for a non-surgical method to treat cataracts, according to a team from the U.S. National Eye Institute (NEI).

Wei Li, a senior investigator in the NEI’s Retinal Neurophysiology Section and co-lead on the study, expressed optimism about the findings. “Understanding the molecular mechanisms behind this reversible cataract process could guide us toward a new treatment strategy,” Li said. The research was published on September 17 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Currently, cataracts are treated exclusively through surgery, with nearly 4 million procedures performed annually in the United States. Cataracts occur when the lens of the eye becomes cloudy, making vision blurry. The search for a non-surgical treatment has been a major goal in ophthalmology for years.

The 13-lined ground squirrel, a common sight in the American Midwest, became a key subject in this research. These squirrels, which have retinas composed primarily of cones (the cells responsible for color vision), were chosen because they experience cataracts during hibernation. When their body temperatures drop to around 39 degrees Fahrenheit, their eye lenses become cloudy. Remarkably, their cataracts disappear once they rewarm, restoring clear vision.

Lab rats, on the other hand, also developed cataracts in low temperatures, but unlike the squirrels, the cataracts in rats were permanent. Cataract formation in cold conditions is common in various species (but not humans) and is thought to be a response to metabolic stress.

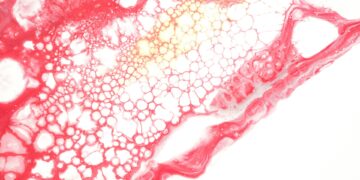

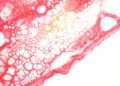

Cataracts in humans typically develop with age, as proteins in the eye lens begin to misfold, clump together, and obstruct light. Age-related decline in the eye’s ability to maintain healthy protein turnover plays a major role in this process.

To better understand this phenomenon, Li’s team collected stem cells from ground squirrels and discovered that the RNF114 protein is vital for proper protein regulation in the eye. During the squirrels’ rewarming process, levels of RNF114 increased significantly, a reaction not observed in the rats.

When researchers injected additional RNF114 into the eyes of rats with cataracts, they found that the cataracts rapidly reversed, similar to the squirrels’ recovery after hibernation. This suggests that boosting RNF114 levels in mammals with cataracts could potentially restore clear vision.

According to the research team, this breakthrough might eventually benefit humans as well. Dr. Xingchao Shentu, a cataract surgeon and researcher at Zhejiang University in China, emphasized the significance of this finding, noting that while cataract surgery is effective, it carries some risks. In many parts of the world, lack of access to surgery makes cataracts a leading cause of blindness. A non-surgical alternative could drastically improve eye care globally.

Discussion about this post