Changing from this diet will benefit you in the long run.

Throughout childhood and adolescence, the human brain undergoes critical development on the path to adulthood, rendering it particularly vulnerable to external influences.

A recent study conducted by USC Dornsrife researchers in California examined the impact of high-fat, high-sugar diets—resembling typical Western dietary patterns—on the brains of juvenile and adolescent rats. The study focused on the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh), essential for memory processes like learning, attention, and arousal, with low ACh levels implicated in Alzheimer’s disease development in humans.

Juvenile and adolescent rats were provided access to an array of foods including high-fat, high-sugar options like potato chips, peanut butter cups, and high-fructose corn syrup, alongside their standard chow and water. Control rats were limited to standard chow and water only. Subsequently, memory tests were conducted on the rats upon reaching young adulthood, assessing their ability to recognize novel objects in familiar settings.

Results revealed significant memory impairments in the rats exposed to the high-fat, high-sugar diet during their developmental stages. Even after transitioning to a healthier diet in adulthood, these memory deficiencies persisted, indicating potential long-term brain damage.

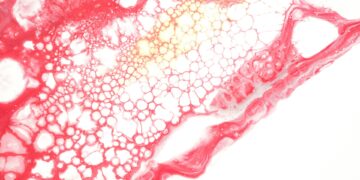

The researchers identified disrupted ACh signaling in the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for memory and learning, in the rats exposed to the unhealthy diet. Scott Kanoski, the study’s senior investigator, emphasized the vulnerability of the hippocampus during juvenile and adolescent development, likening it to the susceptibilities observed in Alzheimer’s disease.

Amy Reichelt, a researcher not involved in the study, highlighted the importance of investigating the effects of diet on ACh signaling in the prefrontal cortex, particularly given its role in executive functions and decision-making. Research suggests that poor dietary habits, especially during adolescence, can detrimentally impact cognitive function, underscoring the significance of early dietary interventions for brain health.

Reichelt referenced ongoing research indicating parallels between dietary influences on neuronal activity in adolescents and those observed in rodents fed a Western-style diet, emphasizing the need for further investigation into the long-term implications of dietary choices on brain function in both humans and animal models.

Discussion about this post