It’s a simple blood test.

An experimental blood test may one day help identify individuals who are at high risk of developing serious lung conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This test examines a panel of 32 proteins in the blood that are most predictive of a person’s likelihood of experiencing a rapid decline in lung function, according to research recently published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

People with higher scores from the blood test face significantly increased health risks: an 84% higher chance of developing COPD, an 81% higher risk of dying from respiratory diseases like COPD or pneumonia, a 17% increased likelihood of being hospitalized for respiratory issues, and a 10% greater chance of experiencing symptoms such as coughing, mucus production, or shortness of breath.

Dr. Ravi Kalhan, a pulmonary medicine professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, noted the importance of such a tool. “We currently lack a simple method to assess whether a patient is on a steep trajectory of lung function decline,” Kalhan said. He emphasized that a blood test could allow for earlier interventions that might improve long-term lung health.

COPD, which includes conditions like emphysema and chronic bronchitis, restricts airflow to the lungs, making breathing difficult for those affected. While there is no cure, COPD can be managed with proper treatment. The test was developed using data from a 30-year study involving nearly 2,500 adults in the U.S., during which participants underwent lung function tests multiple times. Out of the participants, 138 experienced significant declines in lung function.

Researchers analyzed blood samples collected at the 25-year mark and identified 32 proteins that were linked to lung function decline. These proteins were then used to create a score predicting the likelihood of future lung problems. The accuracy of the test was confirmed when it was applied to data from over 40,000 adults from two earlier studies, successfully identifying those at the greatest risk.

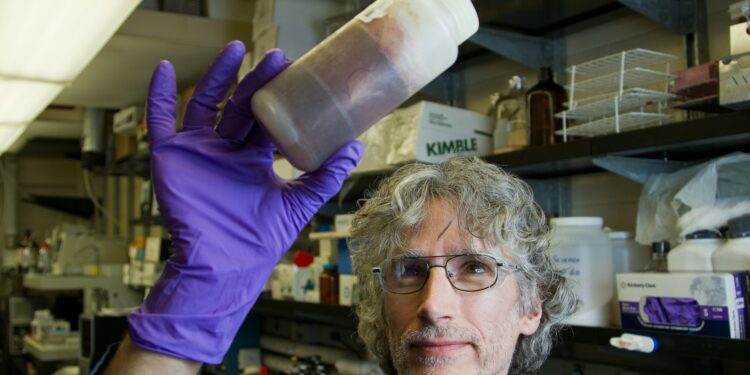

Lead researcher Dr. Gabrielle Liu of UC Davis Medical Center compared this approach to using cholesterol levels to assess heart attack risk. Although the test still needs to undergo further clinical trials before it can be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), James Kiley, director of lung diseases at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, believes it holds promise for identifying patients at risk for severe respiratory disease and complications.

Discussion about this post