It might be wise to start fasting.

Fasting diets, popular for their purported health benefits, may have gained scientific support, according to researchers at the University of Cambridge. The team, led by Clare Bryant from Cambridge’s department of medicine, believes they have identified the mechanisms through which fasting reduces bodily inflammation. Their findings, published in the journal Cell Reports, suggest that prolonged periods without eating trigger an increase in arachidonic acid, a blood chemical with anti-inflammatory properties.

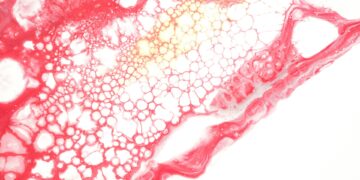

The researchers focused on the “inflammasome,” a cellular alarm system that initiates inflammation as the body’s defense mechanism against injury or illness. However, inflammatory processes can become dysfunctional, contributing to various diseases. The NLRP3 inflammasome, in particular, has been linked to conditions like obesity, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s disease.

While it has been known that fasting diminishes inflammation, the underlying reasons were unclear. The research involved analyzing blood samples from individuals who underwent a 24-hour fast, revealing an increase in arachidonic acid levels, a blood lipid. Lab experiments further demonstrated that arachidonic acid suppressed the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome, contrary to previous beliefs.

Clare Bryant explained that understanding the potential link between diet and inflammation, especially the harmful type associated with Western high-calorie diets, is crucial. Although the effects of arachidonic acid are short-lived, the study contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the health benefits of calorie restriction.

While it remains challenging to determine if fasting can prevent or treat diseases due to the transient nature of arachidonic acid’s effects, Bryant suggests that regular fasting over an extended period could potentially reduce chronic inflammation associated with various conditions. The study raises the intriguing possibility that overindulgence in high-calorie foods might enhance inflammasome activity, contributing to the development of diseases. Bryant speculates on a “yin-and-yang effect,” where both too much and too little of certain elements could influence inflammasome activity, with arachidonic acid playing a role in this delicate balance.

Discussion about this post